Author: Ivan Bogdanov, Technical Writer at HOSTKEY

In one of our previous article, we discussed a cloud-based project that cost just a hundred euros. Imagine how things have changed since then: the number of users has surged, the load on the system has increased tenfold, and now the auto-scaling mechanism is regularly launching 8–10 Node.js instances. Although it works well, the monthly bill has become quite expensive and continues to rise steadily. At some point, you might wonder, “What if I just used a regular server instead?”

This is a classic example of how a project evolves over time. Cloud computing is perfect for getting things started—fast, flexible, and without requiring significant capital investment. However, once the load becomes stable and predictable, the cost structure changes. A dedicated server with 4 cores, 32 GB of RAM, and a RAID storage system (using SSDs) costs €45 per month (or €36 if you pay for a year). With a constant load, this option is significantly more cost-effective than maintaining a cloud cluster with multiple instances.

What is a Dedicated Server?

A dedicated server (often referred to as a “dedic” in layman’s terms) is a physical server located in a provider’s data center that is rented entirely for your use. It’s not a virtual machine whose resources are shared with other users; rather, it’s a standalone system with its own processor, memory, and storage devices, all dedicated exclusively to you. You don’t have to compete with dozens of other clients for CPU time, and there’s no performance degradation due to neighboring services running resource-intensive tasks (such as neural network training). The resources are predictable, and the performance is stable.

Sounds perfect, but that’s where the fun begins. “Renting a server” is similar to “buying a car”—but which type of car? A sedan for urban use, an SUV for off-road conditions, or a sports car for racing tracks? Similarly, there are various types of dedicated servers:

- Bare-metal servers: Designed for maximum performance, these offer the most control over system configuration.

- Managed servers: Ideal for those who don’t want to worry about administrative tasks.

- GPU servers: Optimized for machine learning applications that require intensive computational power.

- Storage servers: Designed to handle large amounts of data.

The choice of server depends on your specific needs, budget, and the level of technical expertise you’re willing to invest in administration.

To help you make an informed decision, let’s take a look at the main types of dedicated servers:

|

Server Type |

Brief Description |

Hardware Configuration |

Use Cases |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bare-metal (Physical) |

A physical server dedicated to a single customer, with no virtualization. |

High-performance CPUs (e.g., Xeon/EPYC), large RAM, fast storage (NVMe/SAS/SSD), and RAID. |

Heavy-duty apps like databases or critical web services. |

Maximum performance; full resource access. |

None listed. |

|

Managed |

Provider handles monitoring, backups, updates, and 24/7 support. |

Any config based on SLAs and backup needs. |

Companies without IT expertise or needing SLAs. |

Reduced workload; pro support and security. |

Higher cost. |

|

Unmanaged/Self-managed |

The customer manages installation, updates, and all aspects. |

Standard dedicated server; customizable OS/software. |

Experienced admins optimizing for specific needs. |

Lower cost; full control. |

Requires expertise. |

|

GPU Servers (Computing Accelerators) |

Equipped with powerful GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100/H100, RTX). |

Multi-core CPUs + multiple GPUs, NVMe storage, advanced cooling. |

ML training, rendering, scientific simulations. |

Faster parallel computations; AI/graphics essential. |

High power/cost; specialized use. |

|

Storage-optimized (NAS/SAN/NVMe) |

Optimized for capacity/reliability: NAS (files), SAN (blocks), NVMe (IOPS). |

Multiple HDDs/SSDs (incl. NVMe), RAID, large memory caches. |

Archiving, multimedia, large datasets, backups. |

High capacity/reliability; optimized IOPS/throughput. |

Less compute-focused. |

|

HPC/Compute-optimized |

Designed for heavy computing and clustering. |

Multi-socket CPUs, large ECC RAM, NVMe, high-speed networks. |

Scientific research, data analysis, computations. |

Extremely high performance. |

Needs specialized infrastructure/software. |

|

Gaming/Low-latency |

Optimized for low latency and high network throughput. |

High-frequency CPUs, RAM, NVMe, geo-distributed locations. |

Online games, real-time apps (e.g., MMOs). |

Low latency; DDoS protection; gaming-ready. |

Gaming-specific; may lack general versatility. |

|

Colocation |

Place your hardware in a data center for space/power/networking. |

Any hardware you provide; full config control. |

Full infrastructure control and compliance needs. |

Complete hardware control; flexible. |

You provide/maintain hardware. |

Architecture: Everything on the same hardware

The fundamental difference from a cloud solution is that we no longer distribute components across different virtual machines. Everything resides on a single physical server, yet it remains isolated from each other:

Key Differences from VPS Architecture:

|

Feature |

VPS (3 Servers) |

Dedicated Server (1 Server) |

|---|---|---|

|

Network: |

External IPs, inter-server communication |

Everything on localhost |

|

Database: |

MySQL on a separate VPS |

PostgreSQL locally |

|

Caching: |

None |

Redis for the /restaurants service |

|

APIs: |

1 Node.js process |

4 processes via PM2 |

|

Proxy: |

None |

Nginx with load balancing |

|

Security: |

Firewalls on each VPS |

Single firewall, managed by Nginx |

|

Cost (Eur/month): |

10.5 |

45 |

Server Configuration and Performance Tuning – A Real Assessment of Complexity

I won’t go into detail about the entire deployment process, but let’s be honest: it’s not as simple as just “three clicks” in the cloud. Configuring a dedicated server requires knowledge and time; I don’t want to give the impression that this is a straightforward task.

The process starts with basic server security measures. You need to set up the UFW firewall, install Fail2Ban to prevent brute-force SSH attacks, generate SSH keys, and create a swap file. This should take about 30 minutes if you know what you’re doing. Next comes installing PostgreSQL version 16, and that’s where things get interesting. The installation itself takes around five minutes, but then you have to understand various parameters such as shared_buffers, how to properly set effective_cache_size based on your 32 GB of RAM, what to do with work_mem, and why random_page_cost for SSDs should be set to 1.1 instead of the default 4.0. Every parameter affects server performance, and improper configuration can significantly reduce its potential. This involves spending an hour or two studying the documentation.

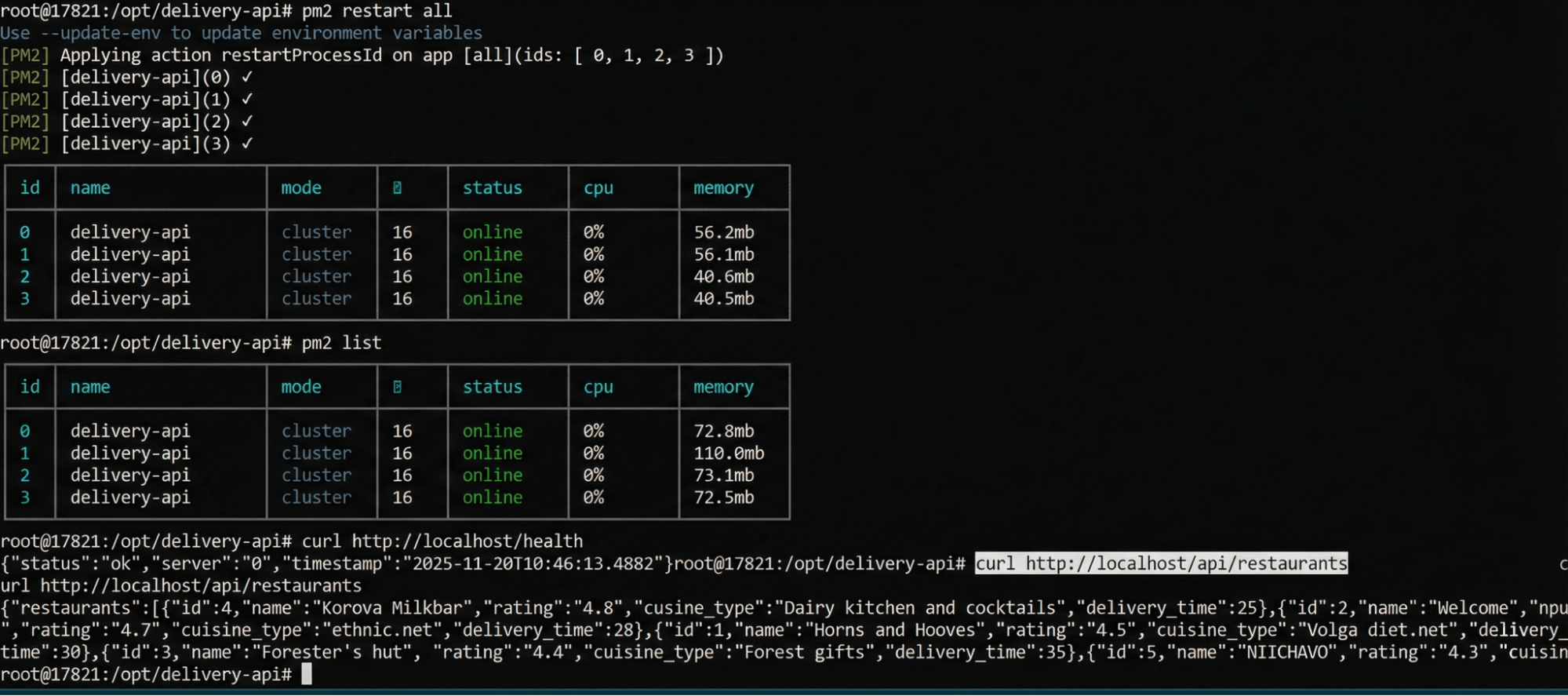

Setting up Redis is relatively easier; the main task here is understanding the cache eviction policies. Do you need persistent data storage on disk or should everything be kept in memory? Which strategy to choose – allkeys-lru or volatile-tti? Another 30 minutes are needed to understand and configure Node.js and PM2 (Process Manager 2). Setting up a cluster of four nodes takes about an hour, including configuring automatic restarts during system reboots, proper logging, and log rotation. With PM2 in place, you’ll have four Node.js processes running in cluster mode, ready to handle requests through Nginx.

Using Nginx as a reverse proxy is another topic altogether. You need to configure proxy settings for four Node.js processes, choose a load balancing strategy (in our case, least_conn), set connection timeouts and keepalive options, and ensure that the headers are correctly transmitted. If SSL is required, you’ll need to add an extra hour for obtaining certificates from Let’s Encrypt as well as setting up redirects. Finally, there’s Prometheus with Grafana: you have to install both tools, configure scrape targets for all components, and create basic dashboards for monitoring purposes. It will take another hour or two, but the monitoring and visualization capabilities are well worth it.

Real-time? For an experienced DevOps specialist who knows these technologies and simply configures them for a specific case, it takes 4–6 hours, including testing and debugging. For a developer with basic Linux knowledge who has to Google half of the commands and read documentation, it’ll take a day or two. For a beginner encountering production-level Linux server setup for the first time, it’ll take three to five days, considering learning and fixing errors.

The most important thing is to understand the basics of Linux: how the file system works, access rights, and systemd services. You need to know basic security concepts—how SSH works, why a firewall is needed, and how to set up fail2ban. You should also understand how web servers and reverse proxies function, as well as the fundamentals of SQL and database management systems (DBMS). You must be able to set up monitoring and troubleshoot issues when something goes wrong.

This isn’t a trivial tutorial project; it’s a production stack that requires responsibility. If the server crashes at 3 a.m., you’ll have to fix it yourself. The tech support from the provider of the dedicated server will only replace the damaged hardware, but figuring out why PostgreSQL failed or why the memory ran out is your own task.

Testing

After setting up the server, it’s time to check how well it performs under real-world load. The purpose of testing isn’t just to get pretty numbers in a report; it’s to understand the system’s limitations, identify bottlenecks, and ensure that everything works stably under stress. We run two types of tests: a latency test (sequential requests to measure the actual response speed) and a load test (multiple clients working simultaneously to simulate real-world traffic).

Methodology

All tests are executed from a client machine using PowerShell scripts, which simulate real users with varying levels of activity. This is crucial because we’re not just running Apache Bench locally; instead, we create a real network load over the internet. The test target is the URL /api/restaurants, which retrieves a list of restaurants from PostgreSQL and caches the results in Redis for 60 seconds. Additionally, each request incurs a simulated CPU load (100,000 mathematical calculations).

Latency Test: Measuring Pure Speed

The first test involves sending 100 sequential requests with a 50-millisecond delay between each one. The goal is to measure the system’s minimum possible latency in a scenario without any resource contention.

|

Metric |

Value |

|---|---|

|

Successful Requests |

100/100 (100%) |

|

Average Latency |

58.23 ms |

|

Median Latency |

56.32 ms |

|

P95 |

60.17 ms |

|

P99 |

62.24 ms |

|

Maximum Latency |

209.19 ms |

|

Standard Deviation |

15.24 ms |

Note: 99% of requests are processed within 50–100 milliseconds, which is very fast for an API that interacts with a database. A single request with a latency of 209 ms is considered normal and may be due to garbage collection, cache misses, or temporary CPU overload. The low standard deviation of 15.24 ms indicates that the system is running stably.

Multi-Client Test: Simulation of Real-World User Behavior

The second test involves 10 concurrent clients making requests over a period of 4 minutes, with a delay of 10 milliseconds between each request. This simulates a moderate but continuous level of load on the system.

|

Metric |

Value |

|---|---|

|

Test Duration |

253 seconds (4 minutes and 13 seconds) |

|

Total Requests |

30,494 |

|

Successful Requests |

30,494 (100%) |

|

Errors |

0 |

|

Average RPS (Requests Per Second) |

120.48 |

|

Minimum Latency |

53.02 milliseconds |

|

Average Latency |

57.32 milliseconds |

|

Maximum Latency |

342.33 milliseconds |

|

Requests per Client |

~3,049 |

The server handles a rate of 120 RPS (Requests Per Second) without any errors. The average latency has not changed significantly compared to when handling individual requests (57 ms vs. 58 ms), which indicates good scalability. Although the maximum latency has increased to 342 ms, it is still within an acceptable range; this may be due to competition for connections to PostgreSQL or instances where the Redis cache ran out of capacity.

The Role of Redis as a Cache

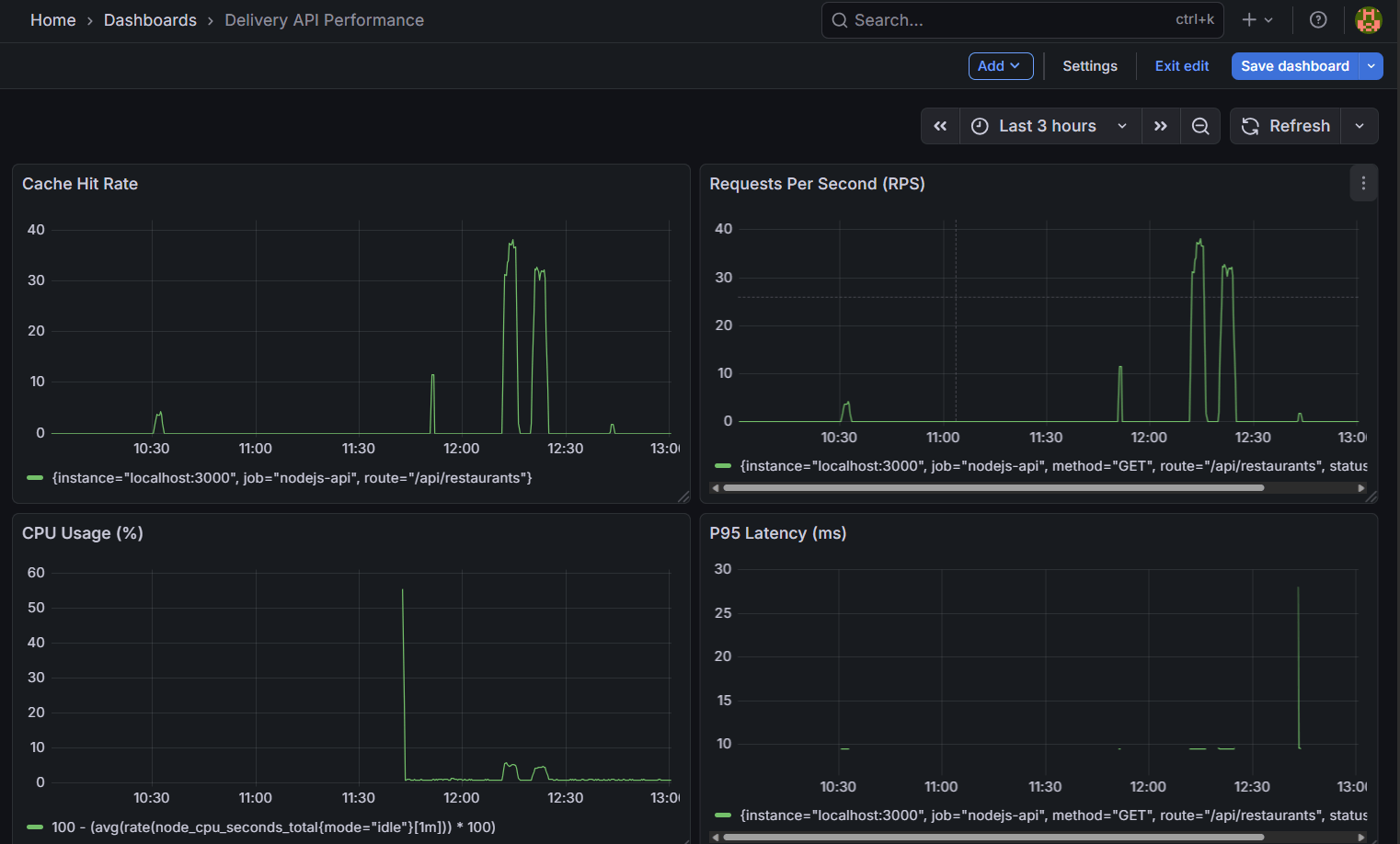

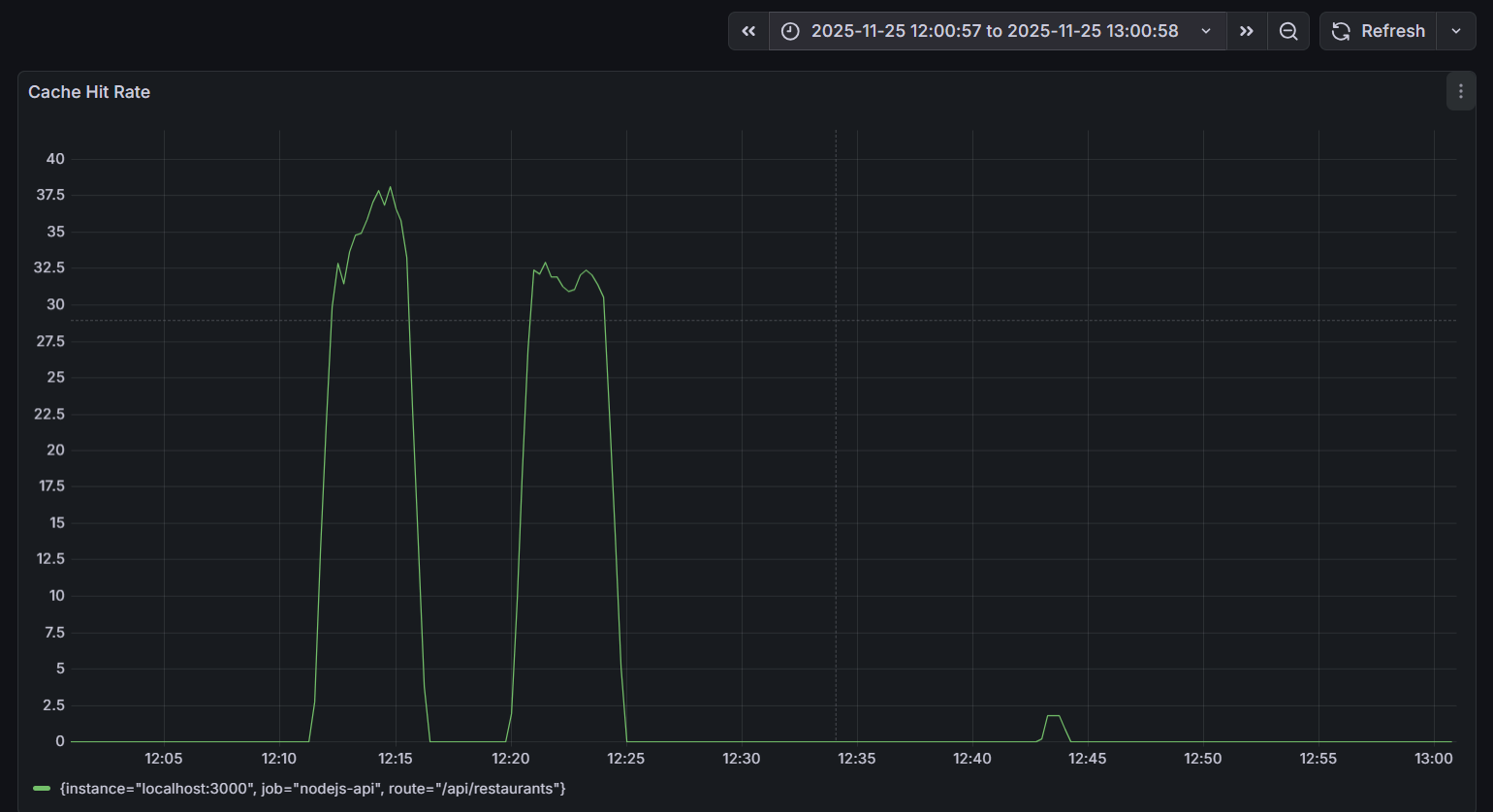

The impact of Redis on performance deserves special attention. The Cache Hit Rate chart during the testing period shows two distinct peaks of activity:

Redis cache requests processed in memory are significantly faster than PostgreSQL requests from disk (with an average latency of 57 milliseconds). At peak times, when there are 37 cache hits per second out of a total of 120 RPS (requests per second), this means that approximately 30% of the requests are greatly accelerated, reducing the overall load on the database.

Comparison with Cloud Architecture

I’d like to remind you that in the cloud version, we had three virtual machines for around 1000₽ per month, which provided similar functionality. However, a dedicated server costing €45 offers excellent performance, more stable latency, built-in Redis caching, full control over the configuration, and predictable costs. The trade-off is additional time spent on setup, administration, and monitoring.

In practical terms, the numbers support the economic viability of switching to a dedicated server under steady loads, but only if you have DevOps capabilities for configuration and maintenance. With the right configuration, the dedicated server performs faster and more stably than the cloud, although it requires the expertise to set up and maintain such a system.

Key Takeaways

Our experiment revealed two things simultaneously, and both are true. Cloud solutions aren’t always more expensive; for initial projects, for unpredictable workloads, or for teams without DevOps experience, using the cloud is often the most suitable and even the only practical option. On the other hand, dedicated servers (on-premises) haven’t become obsolete and are not overly complex either; they can be more cost-effective and perform better for stable workloads, for teams with DevOps capabilities, or for projects with predictable traffic patterns.

The primary mistake in comparing these options arises from making decisions based on superficial factors like hype or price alone. For example, choosing the cloud simply because everyone else is using it may not be a sound strategy; similarly, focusing solely on cost savings without considering potential time costs can lead to suboptimal choices.

We started with three cloud-based virtual machines for a low cost and gained valuable experience in API development and infrastructure management. Later, we switched to a dedicated server, which provided significantly better performance at lower expenses, especially under constant load conditions. However, the transition required careful setup, debugging, testing, and ensuring all systems were properly configured and monitored.

Dedicated servers offer more control but also require greater administrative effort and responsibility. They deliver higher performance due to dedicated resources, but their setup and maintenance are more complex. Cloud services, on the other hand, provide a predictable cost structure, though they may require handling unexpected issues.

If you’re unsure, it’s generally better to begin with the cloud. This approach is suitable for most projects as it allows you to get started quickly and focus on your core business goals. Only when your project grows, your workloads become more stable, and your team has DevOps expertise should you consider migrating to a dedicated server. Such a decision should be based on a thorough understanding of all the relevant trade-offs.

In summary, infrastructure should serve your business needs, not the other way around. Choose the solution that best aligns with your goals and priorities—whether it’s the cloud or a dedicated server.