Author: Ivan Bogdanov, Technical Writer for HOSTKEY

In today's world, the term "cloud" has become so commonplace that we use it without really stopping to consider what exactly lies behind this concept. We store photos in the cloud, work with documents through cloud services, and watch movies on streaming platforms—all thanks to cloud technologies. But what exactly do cloud computing technologies entail from a technical perspective?

According to ISO/IEC 17788-2014, cloud computing is defined as "a paradigm for providing network access to a scalable and flexible pool of shared physical or virtual resources, with self-service and management capabilities available on demand." In other words, it's not just a remote data storage solution; it represents a complete ecosystem that has transformed the way computing power is used.

What is cloud computing, and how does it differ from traditional hosting?

The main appeal of cloud computing lies in its key features. The NIST standard identifies five fundamental characteristics of cloud services, while the ISO/IEC 17788 standard further elaborates on this terminology, specifically addressing the concept of multi-tenancy (multiple users sharing the same infrastructure). As a result, you may find various lists that include either five or six features; this is merely a matter of how these characteristics are presented, not a contradiction.

The first and perhaps most important characteristic is self-service on demand. Imagine you don’t need to call technical support, fill out forms, or wait for a long time to obtain access to additional servers. Users can allocate and release resources independently through APIs or web interfaces, without any direct intervention from the service provider. In practice, this process is extremely fast—virtual machines can be set up in minutes, or even seconds. However, more complex managed services, such as databases, may take a bit longer to configure.

The second characteristic is broad network access. This means you can work with cloud services from any device (smartphone, tablet, or desktop computer) and from anywhere in the world where there is an internet connection. Both physical and virtual resources are accessible over the network through standard mechanisms, making it extremely convenient to use these services.

The third characteristic is resource pooling. Service providers consolidate physical resources into a shared pool and then allocate them logically to individual users. In essence, multiple users share the same infrastructure, but their data and applications remain completely isolated from each other. You don’t need to know where your data is physically stored, as the system automatically optimizes resource allocation. However, if you require additional isolation for compliance or licensing reasons, providers offer dedicated hosting options.

The fourth characteristic is rapid elasticity and scalability. Cloud platforms allow you to easily increase or decrease resources as needed. To achieve automatic scaling, you must configure relevant policies and auto-scaling mechanisms. For example, if your online store suddenly experiences a surge in traffic, the platform will automatically create additional instances to handle the increased load. Once the demand subsides, these extra resources are removed seamlessly, and you don’t have to pay for them. Without such automation, scaling would not be possible.

The fifth characteristic is measurable service delivery. Cloud services are billed based on actual usage, similar to how you pay for utilities like electricity or water. The unit of measurement varies; some services are charged per second (e.g., AWS EC2), while others are priced per hour, per month, or per amount of storage used. It’s important to understand the billing model for a specific service and your location.

The sixth characteristic is multi-tenancy. According to ISO/IEC 17788, physical or virtual resources are allocated in a way that ensures the data and applications of different users remain completely isolated from each other. This ensures the security and confidentiality of customers sharing the same infrastructure.

Three Key Differences Between Cloud Computing and Traditional Hosting

Let’s take a closer look at what makes cloud computing distinct from traditional hosting or managing your own servers in a data center.

- Delegation of Responsibility: The cloud service provider manages the physical infrastructure and basic services, such as hardware, networks, cooling systems, and power supply. If a disk fails, a cable is damaged, or any other hardware issue arises, it’s the provider’s responsibility to fix it. This is known as the Shared Responsibility Model: the provider is responsible for the security of the cloud infrastructure (physical components, hypervisor), while the customer is responsible for the security within the cloud (configurations, data, access controls, encryption). It’s important to understand that this doesn’t mean you don’t need specialists at all; you still need DevOps engineers, SecOps professionals, and cloud architects to ensure proper, secure, and cost-effective operation.

- Speed of Deployment and Automation: The difference is especially evident when you need to scale your resources. With traditional hosting, the process involves identifying that a server can’t handle the load, submitting a request for a service upgrade to the provider, waiting for approval and activation, and then migrating data. This entire cycle can take days or even weeks. In the cloud, this process is automated: a script via an API creates a new instance, deploys the application from an image, and adds the server to a load balancer—all in just minutes. Moreover, the entire process can be fully automated based on triggers from monitoring systems.

- Payment Model and Budget Flexibility: With traditional hosting, you purchase computing power in advance for a long period. For example, a VPS costing $60 per month runs 24/7, even if it’s only used for 8 hours a day; the remaining time represents wasted money. In the cloud, you can pay on demand: if you need a virtual machine for a few hours of testing, you only pay for those hours. This offers greater budget flexibility and reduces financial risks for startups, as they don’t have to invest large sums in infrastructure upfront. They can start with minimal resources and scale up as needed.

It’s these three features that make cloud computing more than just “remote servers hosted somewhere on the internet.” Cloud computing represents a completely new approach to managing computing resources, providing flexibility, speed, and cost efficiency that are unattainable with traditional models.

Comparative Table: “Cloud” vs “Traditional Hosting”

|

Parameter |

Cloud |

Traditional Hosting (VPS/Shared/Dedicated) |

|---|---|---|

|

Payment Model |

Pay-as-you-go (hourly/minutely); pay-per-use |

Mostly fixed monthly/yearly rate; prepaid for a set of resources |

|

Deployment Time |

Minutes – instance/service created via panel/API |

Minutes to hours/days; often requires manual configuration or waiting for dedicated server setup |

|

Scalability |

Horizontal/vertical; automatic (autoscale, load balancers) |

Usually manual: changing plans or rebuilding servers; no built-in autoscaling |

|

Service Level/Ecosystem |

Rich: managed databases, object storage (S3), Kubernetes, functions, CDN, ML services |

Limited: virtual machines and basic additional options; managed services less common |

|

Automation & APIs |

Complete API/SDKs, IaC (Terraform/CloudFormation), CI/CD integrations |

Limited APIs; automation possible but often requires custom solutions |

|

Reliability & Regions |

Multiple regions/zones; automatic replication, cross-regional deployment |

Usually a single host/data center; availability depends on provider’s equipment |

|

DevOps Experience |

Requires/benefits from DevOps practices, IaC, monitoring, and FinOps |

Suitable for less automated management; easier for beginners with smaller projects |

|

Control & Isolation |

Resources shared among multiple clients in public clouds; dedicated to one company in private clouds |

Dedicated servers provide more control and isolation by default |

|

Cost Predictability |

Less predictable without proper controls (spot pricing possible); costs are fixed monthly |

Fixed monthly expenses, easier budget planning |

|

Performance & Latency |

Good for scalable loads; peak performance varies by instance type |

More stable and predictable on dedicated servers for latency-sensitive tasks |

|

Security & Responsibility |

Many managed services reduce operational overhead (updates, backups, replication) |

Most operations fall on the client (patches, databases, configurations) |

|

Ideal Use Cases |

Startups, microservices, variable traffic, ML/Big Data, CI/CD, global services |

Simple websites, constant loads, projects with predictable budgets, or those requiring full control/isolation |

Architecture: What and Why to Deploy

Let’s imagine a scenario where we want to develop an application to target the Forbes list of companies. Our budget is set at $25 per month. After evaluating various options, such as selling WinRAR licenses or gaming accessories for MacBook users, we decided on developing an API for a food delivery service. We will be implementing a classic backend design with predictable peak loads.

The daily workload follows a pattern: a high demand during lunch (12:00–14:00) and dinner (19:00–21:00), while the rest of the time, the load is minimal.

What Our API Can Do

GET /api/restaurants #Returns a list of restaurants (frequent request, cached)

GET /api/menu/:id #Retrieves the menu for a specific restaurant (moderate request)

POST /api/orders #Creates a new order (heavy request involving transactions)

GET /api/orders/:id/track #Tracks the status of an order (frequent request)

GET /health #Performs health checks for system monitoring

GET /metrics #Provides metrics data for PrometheusMinimalist Architecture

The core principle of cloud computing is to start with the minimum amount of resources and scale up as needed. Therefore, our initial configuration is designed to be as simple as possible. We will be using three types of servers, and the general layout is as follows:

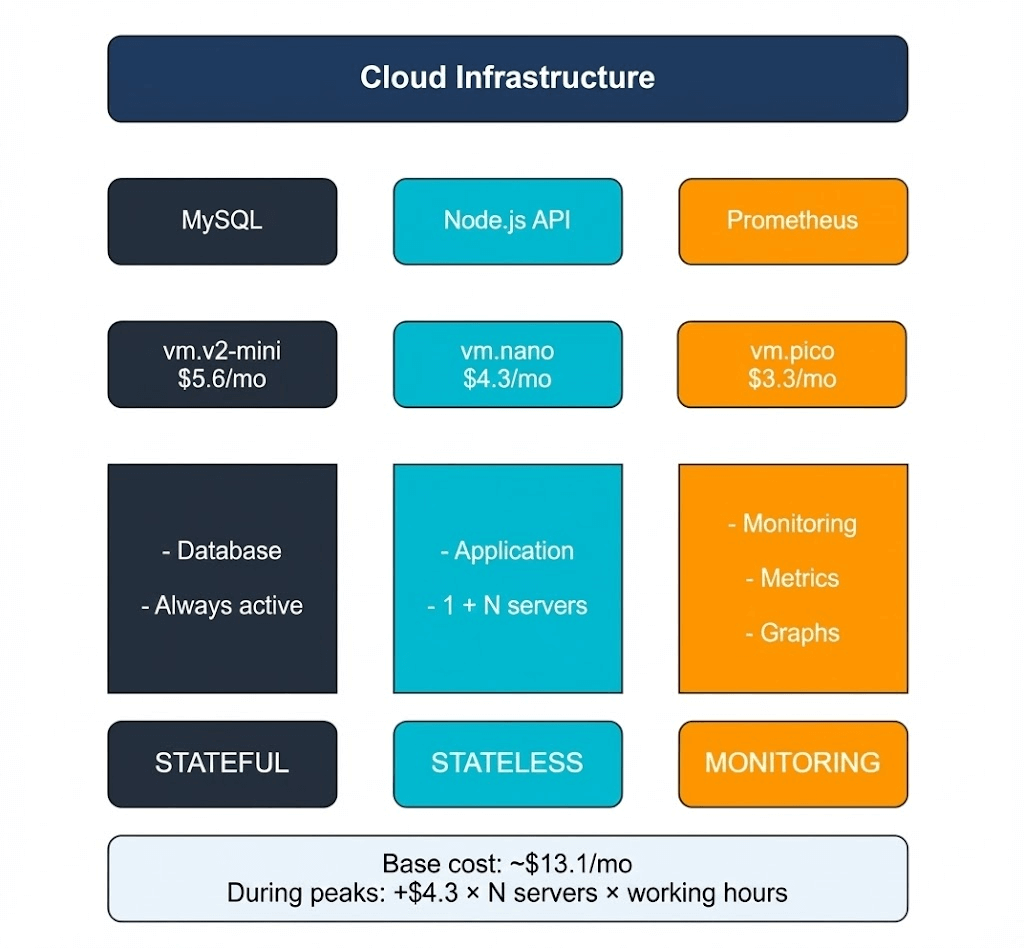

Our infrastructure consists of three independent servers, each performing a specific role—this separation is intentionally designed for efficiency.

- MySQL Server (vm.v2-mini, $5.6/month): This is the only stateful component in the entire system. It stores critical data, such as a directory of five restaurants, a menu with 125 dishes, and a record of past orders. Since the database cannot afford any errors, it’s hosted on a dedicated server with predictable performance capabilities. We’re using MySQL 8.0 with the InnoDB engine, which has been proven to be reliable for handling transactions and foreign keys. Indexes are created on frequently accessed fields (e.g., rating and restaurant_id) to ensure fast query times even as data volumes increase.

- Node.js API Server (vm.nano, $4.3/month): This server serves as the brain of our application, handling all business logic. It processes incoming requests—providing lists of restaurants, generating menus, and managing order placement while checking dish availability and validating user input. A key feature of this server is its statelessness; it does not retain any information between requests, as all data is stored in the database. This means we could easily launch five more instances without any need for synchronization. In the /api/restaurants endpoint, we’ve included a computationally intensive task (calculating 100,000 square roots) to simulate real-world workloads, such as complex business logic or image processing.

- Prometheus Server (vm.pico, $3.3/month): This server acts as our monitoring tool. In the cloud environment, hardware resources are abstracted, so monitoring becomes crucial for understanding system performance. Prometheus collects metrics every 10 seconds by querying the API servers and tracking metrics like the number of requests processed, response times, error rates, and CPU usage. Without this data, it would be impossible to determine when scaling is needed or where bottlenecks exist. Prometheus itself offers a user-friendly web interface with charts that clearly display performance trends, allowing us to quickly identify performance issues.

Why did we split the system into three separate servers instead of using one powerful one? First, it helps with clarity of responsibility: each component handles a specific task (data storage, request processing, and monitoring). Second, it’s more cost-effective—total monthly costs amount to around $13.1, which is lower than the cost of a single VPS with excessive resources. Finally, this architecture allows for easy horizontal scaling. If we need more processing power for the API, we simply clone the Node.js instance and add it to our load balancer; the database and monitoring systems remain unchanged. This isn’t some trivial example for an article—it’s a production-ready configuration that’s actually used in real-world projects, just on a larger scale.

In summary, this minimalist architecture provides efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and flexibility for future growth.

Testing

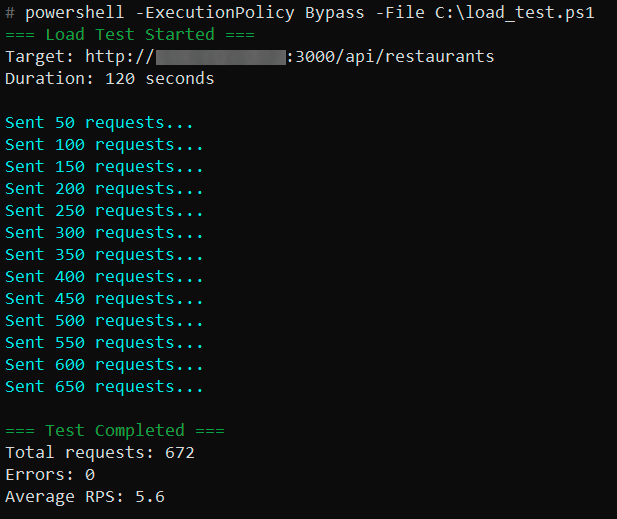

We have prepared a simple PowerShell script that, within two minutes, bombards our API with requests to the restaurant list:

$url = "http://<Server_IP>:3000/api/restaurants"

$duration = 120

$endTime = (Get-Date).AddSeconds($duration)

Write-Host "=== Load Test Started ===" -ForegroundColor Green

Write-Host "Target: $url"

Write-Host "Duration: $duration seconds"

Write-Host ""

$count = 0

$errors = 0

while ((Get-Date) -lt $endTime) {

try {

$response = Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $url -TimeoutSec 5

$count++

if ($count % 50 -eq 0) {

Write-Host "Sent $count requests..." -ForegroundColor Cyan

}

}

catch {

$errors++

}

Start-Sleep -Milliseconds 100

}

Write-Host ""

Write-Host "=== Test Completed ===" -ForegroundColor Green

Write-Host "Total requests: $count"

Write-Host "Errors: $errors"

$rps = [math]::Round($count / $duration, 2)

Write-Host "Average RPS: $rps"This is the most frequently used endpoint in a real-world scenario—users open the application and the first thing they see is the restaurant catalog. Before testing, we made sure everything was working correctly: the API responded to health checks, returned the list of restaurants, and Prometheus indicated a healthy status. The basic checks were passed; we can now start loading the system with additional requests.

# curl http://▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒:3000/health {"status":"ok","server":"api-server-1","timestamp":"2025-11-19T23:00:39.162Z"} # curl http://▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒:3000/api/restaurants {"restaurants":[{"id":4,"name":"Korova Milkbar","rating":"4.8","cuisine_type":"Milk bar & cocktails","delivery_time":25},{"id":2,"name":"Be Our Guest","rating":"4.7","cuisine_type":"Ethnic","delivery_time":28},{"id":1,"name":"Horns and Hooves","rating":"4.5","cuisine_type":"Volga Diet","delivery_time":30},{"id":3,"name":"Forester's Hut","rating":"4.4","cuisine_type":"Forest Bounty","delivery_time":35},{"id":5,"name":"NIICHAVO","rating":"4.3","cuisine_type":"Experimental","delivery_time":40}],"server":"api-server-1","processed":21081692.74615191} # curl http://▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒:9090/-/healthy Prometheus Server is Healthy.The script sends requests with short intervals to simulate the actual user traffic. In 120 seconds, 672 requests were made without a single error. The average rate was 5.6 requests per second. For a small vm.nano server, this is a fairly substantial load, especially since we intentionally included CPU-intensive calculations in the code to mimic real business logic:

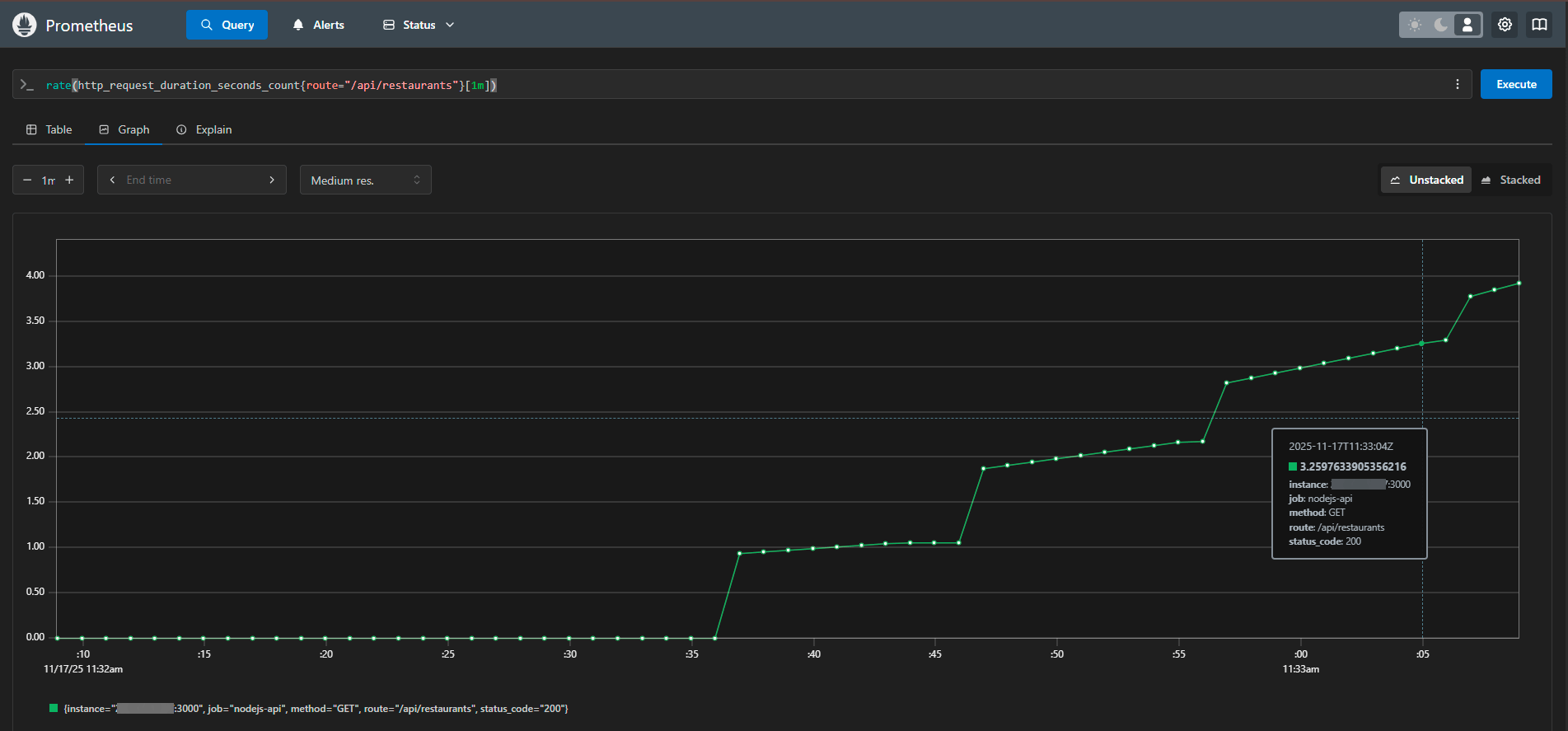

Here’s how the same test appears from the perspective of a monitoring system. The graph shows a smooth increase in traffic from zero to a peak of 3.9 RPS (requests per second), followed by further growth and then a sharp drop after the test ended. There were no failures, timeouts, or any unusual anomalies. The system handled the load steadily throughout the entire period:

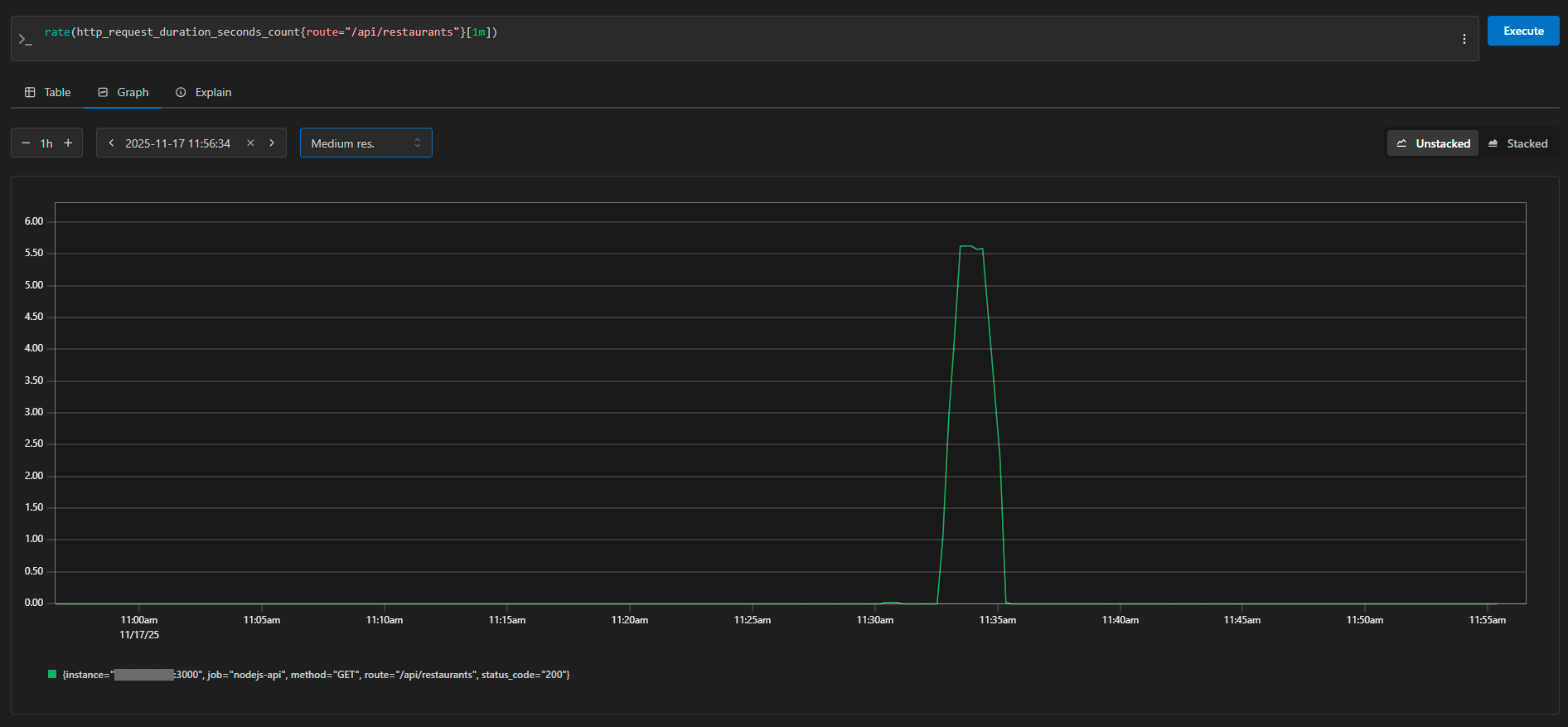

The same graph, viewed over a narrower time frame, demonstrates an ideal load profile—starting from 0 RPS and rising to 5.5 RPS before dropping back to zero. This is the expected behavior during a controlled stress test. In Prometheus, we can see details about each request: the instance (server address), method (GET), route (/api/restaurants), and status code (200). The metrics are collected every 10 seconds, so the graph is both detailed and accurate.

Test Results and the Economics of the Solution

The test results were as expected and promising. The system handled the entire load without any errors, maintaining a steady rate of approximately 5.6 requests per second. Response times ranged from 40 to 130 milliseconds, which is entirely acceptable for user experience, as users won’t notice delays shorter than 200 milliseconds.

Of course, 5–6 requests per second aren’t enough to trigger a surge in sales at Amazon. However, for demonstrating the principles of cloud infrastructure, this is more than sufficient. Our small Node.js server on vm.nano performed admirably, using minimal resources. The database didn’t even become overloaded—its connection pool processed all requests instantly, and the indexes functioned as intended.

In its current configuration, the system can comfortably handle several hundred requests per minute, which is more than enough for a MVP (Minimum Viable Product). But just imagine the traffic increasing tenfold: with a traditional approach, you’d have to urgently purchase a new server, transfer data, and make subsequent adjustments. In the cloud, we simply cloned the API server, added it to a load balancer, and that was it. The database and monitoring tools remained in place.

The basic configuration of three servers costs $13.1 per month. For a startup, this might seem like a significant expense. However, the main benefit becomes evident when traffic varies: our delivery service is actually under heavy load for five hours out of 24 (during lunch and dinner peaks). With a traditional model, you’d have to pay for a server 24/7; in the cloud, we can add additional resources only during peak times. Even with monthly pricing, the flexibility offered by the API-based approach offers significant advantages—for example, we could test the system for a week and only pay for that period. If the project doesn’t succeed, we don’t get stuck with a yearly contract.

In summary, while the initial costs may seem high, the flexibility of the cloud model is invaluable: our delivery service experiences peak loads (5 hours/day) during business hours. With a traditional approach, you’d have to pay for a server continuously; in the cloud, we can scale up resources as needed. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of using APIs is evident—after just one week of testing, we only paid for that time period.

Conclusion: From VPS to the Full Cloud

Our low-budget experiment clearly demonstrated one thing: cloud technologies are not only accessible to corporations with millions in budgets. Even with a minimal configuration, it’s possible to set up a fully functional system that can handle real workloads and is ready for growth.

We intentionally used regular VPSs for our demonstration because the architecture and principles of operation are exactly the same as those in full-scale cloud platforms. The application code, database structure, and monitoring settings are all identical, whether you’re running the system on a VPS or in Google Cloud. The only difference lies in the additional capabilities offered by the true cloud: automatic scaling based on performance metrics, pay-as-you-go pricing (only for the actual usage time), built-in managed services, and out-of-the-box load balancers.

Our VPS setup can be compared to a training vehicle—you learn how to manage systems, understand their principles, and get comfortable with the operations. Once you’re ready, you can move on to a more advanced platform with features like automatic gear shifting, cruise control, and advanced safety systems—the management is still the same, just more convenient and powerful.

Similarly, once you’ve mastered the basics of cloud architecture, you can easily migrate your application to AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, or any other platform. Docker containers run the same everywhere, Prometheus collects metrics according to the same standards, and the business logic of the application doesn’t care where it’s physically hosted.

The cloud isn’t a panacea, nor is it always the best choice. If you have a stable, predictable workload that operates 24/7, a traditional dedicated server might be more cost-effective. If you need complete control over the hardware and minimal latency, a self-hosted solution in a data center is preferable. However, if your product is still in its infancy, traffic is unpredictable, or speed of deployment and flexibility are crucial, the cloud is a natural choice.

The main lesson from our experience is to start with the minimum setup and scale up as needed. There’s no need to set up a large cluster of servers in advance for future use. Start with just three small instances, configure monitoring, and launch your product. Once you have real users, you can identify performance bottlenecks and then expand resources as needed. The cloud gives you the freedom to experiment without taking on significant financial risks.